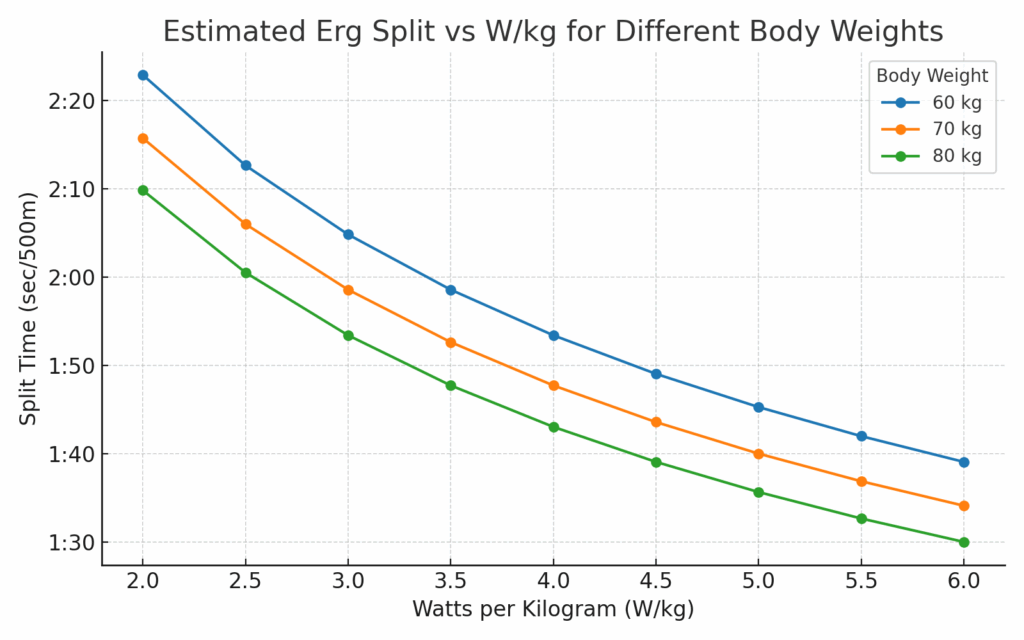

For as long as rowing machines have been part of the sport, split times have been the currency of comparison. Whether it’s the average pace per 500 metres over a 1km trial or the dreaded 2k test, split times are familiar, easy to understand, and have long been the standard for measuring performance. They tell us, in clear numbers, who can move the flywheel fastest. This is useful for ranking raw output and selecting crews in large boats where absolute power is king. But split times have one major limitation — they do not tell us how much power a rower is producing relative to their body size.

That is where watts per kilogram (W/kg) comes in, and in many ways, it’s the metric we should be paying closer attention to. W/kg measures how much power an athlete produces for every kilogram of body weight. This simple adjustment gives a far fairer view of true athletic ability, especially when comparing rowers of different builds. Two rowers might produce identical splits, but if one is 95 kg and the other is 70 kg, the smaller athlete is producing far more power relative to their size — a sign of greater efficiency and strength for their body mass.

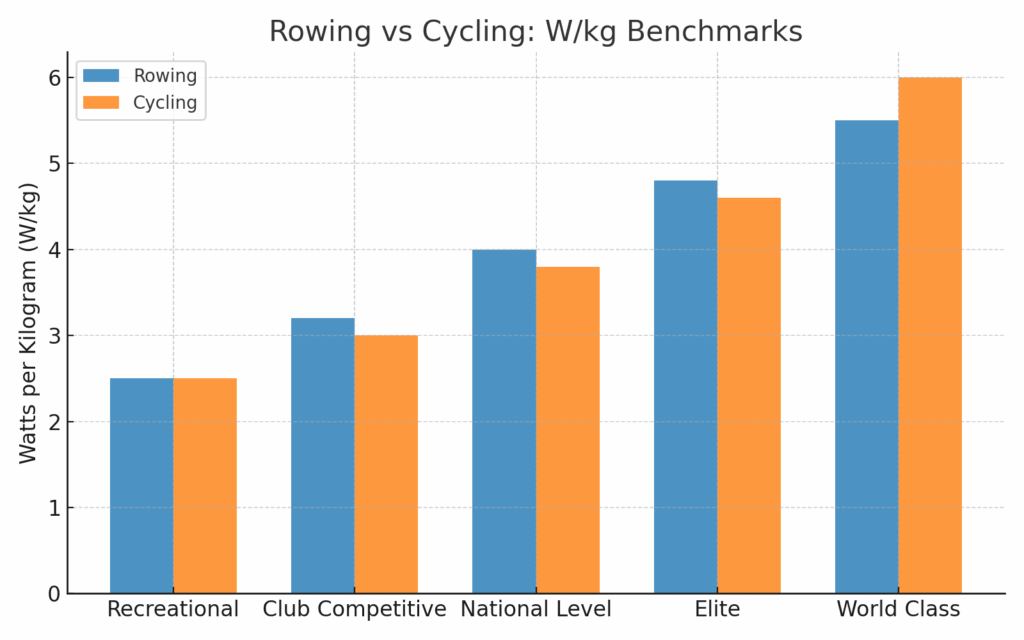

W/kg is nothing new in the world of sport — it has been a cornerstone of performance analysis in cycling for years. In professional road racing, climbing ability is often measured in W/kg, because it determines how quickly a rider can ascend a hill relative to their body weight. Just as in rowing, the physics are clear: the more power you can produce for your weight, the faster you can move over a given resistance. The crossover between the two sports is well known, with many athletes transitioning from rowing to cycling after retirement. One example is Hamish Bond, one half of the legendary New Zealand “Kiwi Pair,” who went on to become a highly competitive cyclist, representing New Zealand at the Commonwealth Games. His success in cycling was built on the same high relative power that made him a dominant force in the boat.

In smaller boats such as singles, doubles, and pairs, W/kg is often a better predictor of boat speed than raw split times. Physics is the reason: smaller boats are more sensitive to total mass and more responsive to rowers who can generate high relative power. This means that the strongest, fittest athletes — the ones who produce impressive W/kg numbers — often deliver more on the water than their split alone would suggest. By focusing solely on splits, coaches risk overlooking these athletes in favour of bigger rowers whose absolute power is high but relative efficiency is lower.

This isn’t to say that split times don’t matter. They remain a vital benchmark for selection, particularly in large crew boats where combined absolute power moves the shell. But pairing split times with W/kg creates a fuller, more accurate picture of an athlete’s capability. W/kg tells you not just who is fast, but who is punching above their weight — literally. It identifies the rowers whose fitness, strength, and efficiency might be hidden behind slower splits caused by a smaller frame.

For coaches, the takeaway is clear: record and track both metrics. Use split times to assess absolute performance, but lean on W/kg when you want to identify the most capable movers in smaller boats or spot developing talent. For athletes, knowing your W/kg as well as your splits can be motivating — it shows your progress in ways the raw pace might not. Ultimately, in a sport where every fraction of a second counts, watts per kilogram gives you context, and context can be the difference between a good crew and a great one.

1 Comment

William Olayos · August 16, 2025 at 9:37 pm

A factor missing in your discussion is the time frame for the graphs. Are they taken as a 500m, 1000m, or 2K split, or something different? I can produce over 400 watts in a maximum output effort (and at 65 kg that translates to over 6 W/kg) while for a 30 minute row, limited to rating 20, I can only manage 150 watts (a very pedestrian 2.3 W/kg). I assume I am somewhere in between, but I would love to know the time parameters used in those graphs.

Definitely love the way you are thinking though. I have always felt I don’t slow most boats I hop into down, and this may give fuel to that opinion!

Great article.