Let me start by saying this clearly: this article, like many I write, will probably stir some emotions. It might surprise, challenge, or even lightly upset some readers, but it’s an important conversation we need to have. And before we go any further, let me be absolutely clear: there is nothing wrong with being a social rower, or enjoying any athletic pursuit purely for its own sake. I admire and encourage that deeply. This piece, however, is written for those who want to compete — athletes whose goal is not just to participate but to push their limits and chase real performance.

You might think that going out on the water with your crew, coach alongside, and running through some drills means you’re training. But here’s the truth: a lot of what people call training is just rowing. Rowing is paddling up and down the river. Sometimes it’s social. Sometimes it’s mindful. Sometimes it’s technically focused. And sometimes it’s just “putting in the miles.” But training — real training — has a specific goal. It’s not about just covering distance or fine-tuning one more stroke detail. It’s about getting faster, getting stronger, and preparing yourself — mentally and physically — to race at your limits. And here’s the uncomfortable truth: going fast hurts.

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve stepped out of a boat after a session or a race and heard complaints: that was a bad row, the boat didn’t feel right, it was messy, it was uncomfortable. But when I look at the numbers — the splits, the times — I see the fastest performance that crew has ever delivered. And still, some athletes aren’t happy. That mindset baffles me. Because if you’re a competitive athlete, the number one goal is speed. Everything else is trivial. In masters rowing, sure, sometimes you get lucky with the draw or win because of the division system or quirks of the regatta format. That can build confidence, but it’s not a true test for a competitor. For real athletes, results are earned through preparation, not chance.

One of the frustrations of being a coxswain in a masters club environment is that you’re rarely attached to a single crew. You jump from boat to boat, crew to crew, rarely able to make a deep impact because there are no structured training crews. But in recent years, I’ve had the privilege of working with a few groups who broke that mould. Two women’s crews, one men’s crew — all masters athletes — who said, “Yes, we want to train together, with focus, for a specific goal.” And once they said yes, they were mine — said with a grin, but meant seriously. They made a commitment — to themselves, to each other, and to me — and once they committed, they became accountable. That’s the moment everything changed.

We trained. We didn’t just row. Every session had structure, in fact the whole program had structure: on the water, off the water, at home. And the results followed. Let’s be clear — “results” doesn’t always mean winning. In masters rowing, luck, entry lists, and combinations often play a role. But in these three cases, we built good, fast crews. Why were they good? The men’s crew were lifetime rowers — former schoolboys and club athletes, one even an Australian junior representative. The women’s crews were newer to rowing but fierce, determined, and willing to work hard. I’m a firm believer in using the tools you have and focusing on what you can change.

And here’s the hard reality for masters athletes: you can’t waste time paddling endless kilometers chasing technical perfection. Your neuroplasticity — your brain’s ability to lock in new movement patterns — isn’t what it was at age sixteen. You simply won’t get there. But you can improve your body’s capacity to work hard. You can improve your brain’s ability to tolerate discomfort, to accept the pain of training and racing.

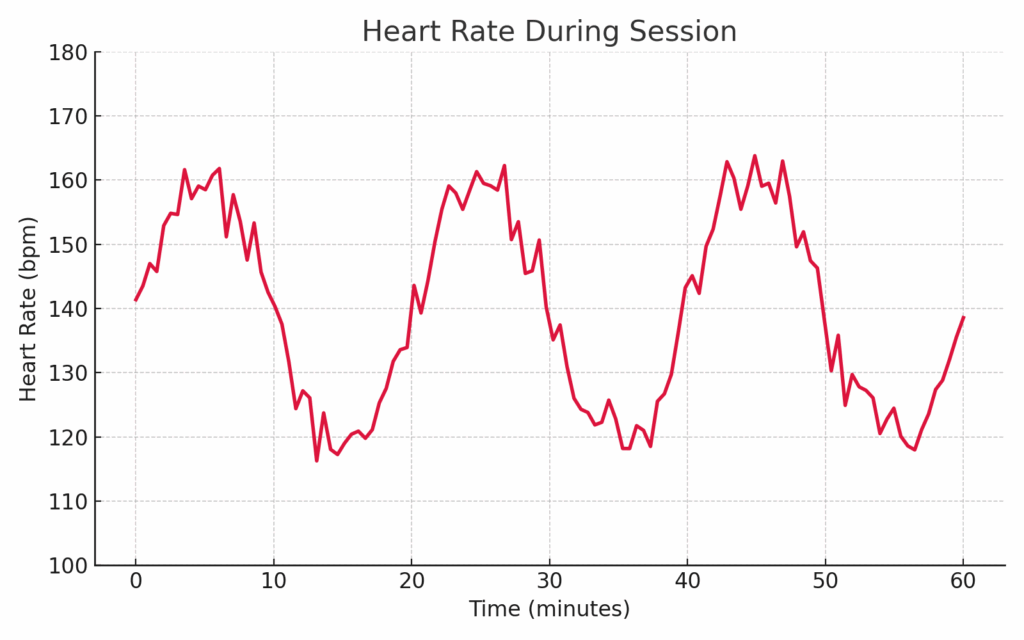

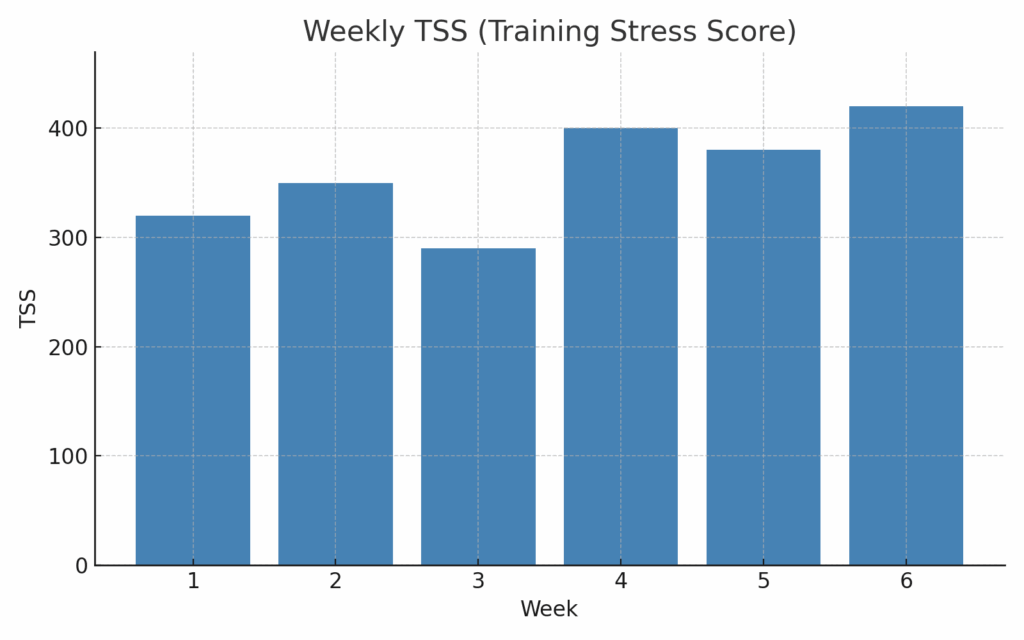

For those wanting the extra comfort of knowledge, here’s something you should seriously consider: get yourself a smartwatch and start tracking your fitness statistics. Oh, don’t tell me it’s too expensive — come on! You spend a fortune going to regattas, on weekends away, race entries, club fees, and many of you even own your own boats. A smartwatch is cheap by comparison! And it’s a small investment that can make a huge difference in your growth as an athlete. I also strongly recommend getting a TrainingPeaks account. This platform gives you real numbers on how your body is coping, how your training is working, and where you need to adjust. Personally, I find TrainingPeaks a vital part of my approach — I follow the numbers closely. After all, TSS (Training Stress Score) doesn’t lie! More than once, I’ve looked at the TSS data after what the coach and crew thought was a solid one-hour “training session” and, well, the numbers revealed it was really just a row. Handy to know, especially if you actually want to improve.

This article isn’t criticising those who want to enjoy the experience of rowing, racing, and community. It’s here to highlight the difference between rowing and training. And the number one difference? It’s not talent. Not age. Not perfect technique. It’s mindset. If you have that inherent competitive streak — if you’re wired to push, to chase, to grind — then understand this: you can’t just row. You have to train. And if you want to give your crew the best possible chance of success, that training has to be hard. There’s nothing wrong with having fun. But if you want to win, it has to hurt sometimes.

At the end of the day, every athlete — no matter their age, background, or experience — has to decide what they want from their sport. There’s enormous value in simply being on the water, enjoying the movement, the company, the rhythm of the boat. But if you have that restless itch inside, that fire that wants to push beyond what’s comfortable, then remember: you’re not out there just to row. You’re out there to train. And training is hard. It challenges you not only physically, but mentally and emotionally.

You’ll doubt yourself. You’ll feel tired. You’ll wonder if it’s worth it. But when the moment comes — when you line up at the start, when you feel the boat lock together in that perfect drive, when you cross the line knowing you gave everything — you’ll know exactly why you chose the harder path. Because that’s the path that makes the difference.

0 Comments